This article focuses on Colonel B.F. Morley (1855-1903), a late 19th and early 20th Century gold mining and smelting industrial pioneer, scientist, professor, and local politician. It is noteworthy that every community in Colorado has its own special historic figure(s). These individuals encompassed a diverse range of professions including miners, storekeepers, politicians, soldiers, explorers, farmers and ranchers, teachers, factory workers, industrialists, conquistadors, librarians, scientists, and tribal chiefs. Too often their names and accomplishments have been relegated, by time and events, to near obscurity. Only a fortunate few, predominantly men, have their names remembered on street signs, community parks, historic buildings, or in the rarest of cases Colorado fourteener summits.

Shavano Intelligence posits that a shared past engenders shared opportunities. We seek to rediscover the often forgotten women and men who made historic and cultural contributions to their communities. The Colonel Morley story serves to provide a better understanding of the life, accomplishments, and key interrelationships of this exceptional individual.

The Early Years

Benjamin Franklin Morley was born on December 3, 1855, in Strawberry Point, Iowa. His father, Sylvanus, a prominent farmer, passed away when Benjamin was two. In 1857, his mother, Mary Louisa, married Edmund Elvidge, a wealthy Iowa storekeeper. The Elvidge family later relocated to Wisconsin, finally settling in Illinois.

Limited information is available regarding Benjamin’s early life and education. However, it is documented that following the death of his father, Benjamin’s uncle, James H. (J.H.) Morley, treated Benjamin as if he were his own son. Newspaper reports indicate that Benjamin resided with his uncle for extended periods, and likely accompanied him on numerous journeys, as J.H. directed railroad civil engineering construction projects across the country. For example, as a teenager, Benjamin resided with his uncle, in Little Rock, Arkansas, where J.H. was the chief engineer constructing the Little Rock to St. Louis rail line. These experiences provided young Benjamin with invaluable life lessons.

J.H. Morley (1824-1889), from a Cambridge University Historic Memorial was a professionally educated and experienced civil engineer. Prior to and after the Civil War, J.H. designed and managed railroad construction projects across southern Missouri, northwest Arkansas, eastern South Carolina, New York, and eastern Kansas. During this era of early railroad expansion, civil railroad engineers encountered many unique challenges and difficulties. Such as overcoming unexpected terrain and engineering obstacles and alleviating significant local community resistance to the railroad. Designing and directing rail line construction required exceptional engineering skill, profound knowledge of geology and terrain, management and leadership expertise, and an ability to rapidly adjust course. According to J.H. Morley, it also required a profound sense of integrity, honor, mutual respect, and understanding for railroad employees and local communities impacted by the railroad.

During the American Civil War, the Confederates offered J.H. a substantial financial incentive to assist their forces in navigating the confusing, meandering waterways and swamps of southern Missouri or, at the very least, to create topographic maps for the use of Confederate military commanders. J.H. declined these offers, aligning his loyalty with the Union. Despite an effort to join the Union Army, he was unsuccessful in securing a suitable position and subsequently opted to forgo military service, embarking on a journey west to the gold fields of Montana.

In a published biography, J.H. recounts his departure for Montana in 1862, providing detailed accounts of the environment, people, native tribes and experiences in this unsettled region. Written in the style of the Journals of Lewis and Clark, The J.H. Biography demonstrated his powerful observational skills and unique abilities to perform in challenging and unconventional environments. Before returning to St. Louis in 1865. J.H. had amassed a considerable fortune in Montana placer gold, providing significant capital for his future gold and silver mine investments in Colorado. The epic adventures of J.H. Morley in Montana, likely had a profound impact on a young Benjamin and probably contributed to a decision, to emulate his uncle in the Colorado gold fields.

In 1873, with the financial backing, influence, and recommendation of his uncle, Benjamin Morley enrolled in the Pennsylvania Military Academy (PMA). PMA was subsequently renamed Pennsylvania Military College (PMC) and is situated in Chester, Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Benjamin Morley excelled at PMC, particularly in the Corps of Cadets, and in 1878 graduated at the top of his class with a degree in civil engineering. J.H. Morley attended the graduation ceremony and encouraged Benjamin to pursue further studies at PMC.

PMC, now known as Widener University, was widely recognized as one of the leading private military colleges in the nation, frequently competing with West Point for academic excellence and attracting students of exceptional talent. Census records indicate that Benjamin continued his studies at PMC between 1878 and 1882, likely pursuing additional qualifications in chemistry and mathematics. In 1882, Morley was appointed as a full professor at PMC, where he taught chemistry, mathematics, and tactics.

In March 1881, Morley enlisted in the Pennsylvania National Guard at the rank of Captain. His unit was activated by the Governor of Pennsylvania and ordered to Pittsburgh to assist in maintaining order during the ongoing regional railroad strikes. Reportedly, his unit provided an official presence to limit violent outbreaks between strikers and railroad security guards. Railroad executives had requested the national guard deployment, but became frustrated when guardsmen, for the most part, did not support the railroad companies by forcibly suppressing the strikers.

On October 1882, Captain Morley resigned his commission, the reasons for the resignation remain uncertain. However, it is plausible that his new professorship position and classroom responsibilities conflicted with his role at the Pennsylvania National Guard. Additionally, Morley acquired his first Chalk Creek Chaffee County, Colorado gold mine that very spring, through a quit claim deed acquisition, while residing in Chester. Of greater significance, in 1880 J.H. had acquired ownership of Chaffee County’s Mary Murphy Mine, along with several other gold and silver mines in the Chalk Creek Mining District. The Mary Murphy acquisition would soon become one of the most prosperous gold mines in Colorado, leaving a lasting and profound impact on J.H. and B.F. Morley.

On July 3, 1882, B.F. Morley married Sarah Elinor Constance DeLannoy in Chester. The ceremony was officiated by Captain James Barton Jr., a Civil War Army officer, fellow Pennsylvania National Guard member, and former classmate of Morley’s. Captain Barton was also the Mayor of Chester. Sarah’s father, Felix DeLannoy, was a former professor of modern languages at the PMA. Sarah received her education in private girls’ schools, potentially one in which her father directed before becoming a professor. Sarah traveled outside the United States to Europe at least once, likely on a tour of Europe and to visit family in Belgium. Her grandfather had served as a judge on the Belgium Supreme Court, and the DeLannoy family had nobility connections across northern France and Belgium.

Following his marriage, Captain Morley played a pivotal role in establishing the PMC Institute of Science and Mechanic Arts. He collaborated with his father-in-law, other PMC professors, and college faculty to achieve this objective. The institute was created to promote the dissemination of general and scientific knowledge among its members and the broader Chester community. Additionally, it was intended to establish and maintain a library, historical records, and a museum in Chester. Widener University has consistently upheld and supported these historic fundamental objectives. By continuing its support to the PMC Museum and dedicating exceptional effort to acquire and preserve a repository of archival records, through Widener’s Wolfgram Memorial Library.

In June 1883, B.F. Morley and Sarah had their first child in Chester. By 1900, they had six children: Sylvanus, Constance, James, Alice, Elinor, and Sarah. Elinor and Sarah were both born in Buena Vista, Colorado. At the request of his father, Sylvanus attended PMC, graduating with a degree in civil engineering before pursuing advanced archaeological studies at Harvard. After graduating from Harvard, Sylvanus became a renowned archaeologist, specializing in Mesoamerican and southwestern United States Anasazi archeology. During World War I, he served in the United States Navy, becoming one of the Navy’s first Central American foreign intelligence collectors. His extensive local contacts, comprehensive area knowledge, and a civil engineer understanding of the terrain and jungle environments made him an invaluable WWI naval collector and intelligence analyst.

According to the Delaware Daily Times, in 1888, B.F. Morley was promoted to PMC Vice President and given the college honorary rank of Colonel. Chester residential records indicate Colonel Morley held the position of college vice president to at least 1893 and possibly longer, despite relocating to Buena Vista, Colorado. It is uncertain whether Colonel Morley was on an extended sabbatical leave from PMC while residing in Colorado. Or if he was simply bestowed with the honorary title of vice president due to his academic regard, familial connections, or significant financial contributions to PMC from wealth acquired while living in Colorado.

The Glory Years

In December 1884, Colonel Morley secured a highly favorable lease to operate and manage the Mary Murphy Mine. The paid lease amount was for a six-year term and required nominal payment of $10,000. The lease executed with the St. Louis Mary Murphy Mining Company, which was wholly owned by his uncle, J.H. Morley. Notably, the Mary Murphy Mining Company required provision of a 25% share of net profits generated from the extraction of gold, silver, and other precious metals from the Mary Murphy, during the six-year lease.

Sixteen days after closing the Mary Murphy lease, Colonel Morley returned to Chester and transferred the Mary Murphy Lode to a newly established company, Golf Mining Company, for $26,000 and $10,000 in cash. The Golf Company, named after a Mary Murphy nearly horizontal mine adit, was managed by Colonel Morley’s local Chaffee County business partner and fellow investor, John Taylor. It is highly probable that Colonel Morley used funds acquired from the Golf-Mary Murphy transaction to conceptualize and design the technologically advanced pyritic smelter he constructed in Buena Vista, in several stages, between 1887-1889.

Between 1880 and 1888, J.H. and the Colonel traveled frequently from St. Louis and Chester to Chaffee County. There they applied business acumen, acquired and sold additional gold mine interests, constructed new mining structures, used scientific knowledge to enhance assaying operations, and enlarged the Mary Murphy. J.H. Morley’s Missouri business partners, civil engineer Henry Flad and his son, St. Louis Water Commissioner and certified civil water engineer, Ed Flad assisted the Morley’s, both technically and probably financially with the Mary Murphy mining operations.

Ed Flad was also active in acquiring controlling and partnership interests in Chalk Creek gold mines, including several mine acquisitions purchased in concert with Colonel Morley. Flad resided in Chaffee County for several years, and functioned as lead assayer for the Mary Murphy Mine. Mine assayers were critically important to gold mining and smelting operations because they determined the economic viability of a discovery and were essential for guiding mining operations. Their specialized analysis removed the guesswork from mining and informed a company’s most critical financial decisions.

Ed Flad provided valuable assistance through his exceptional water engineering knowledge in designing specialized hydro-engineering solutions to channel and divert ground and surface water from Mary Murphy mine shafts and to protect its weather impacted external structures. He likely provided Colonel Morley with a ready source of water engineering expertise in developing the hydro-dam on the Arkansas River which provided water and and eventually electric power to the Morley Smelter and the residents of Buena Vista.

Having owned or been involved with the Mary Murphy since 1880, J.H., Henry and Ed Flad, and the Colonel would have been well-acquainted with the pervasive low to medium grade quality of ore present in the Chalk Creek Mining District and across most of Colorado. This well-qualified mining ownership team would also have had firsthand experience with the inherent challenges of efficiently processing lower quality Rocky Mountain oar. Traditionally, small-scale smelters were often built adjacent to high-mountain mining claims to reduce expensive unrefined oar transportation costs. J.H. Morley had a small-scale smelter operation located adjacent to the Mary Murphy Mine. Such smelters tended to be inefficient, subject to wintertime shutdowns, suffered recurrent breakdowns, and often experienced fuel shortages of coal, coke, and charcoal.

As civil engineers, chemical and metallurgical experts the Morleys and the Flads also understood the financial burdens faced by miners in transporting larger quantities of lesser quality ore to distant refineries. The construction of the rail line to St. Elmo was a watershed event for the Chalk Creek gold miners. Probably precipitating J.H. Morley’s decision to acquire the Mary Murphy and other financially distressed Chalk Creek gold mines. It also directly impacted upon Colonel Morley’s decision to construct the pyritic smelter at Buena Vista.

In the early 1880s, only a few medium to large-scale gold and silver refineries existed in Colorado, such as Denver’s Argo, Pueblo’s Colorado (1st Street), and Leadville’s Arkansas Valley smelters. At that time, these smelters lacked the technological and chemical processing capabilities to efficiently process low-grade sulfide-rich ores found in Colorado. Only the Argo, a reverberatory smelter, employing techniques derived from the Wales Swansea method, could profitably refine a few limited types of sulfide-rich ores. Furthermore, the costs associated with transporting large quantities of sulfide and quartz gangue-heavy Chalk Creek ores to these in-state smelters at scale were prohibitively expensive, resulting in a high economic mine failure rate.

In 1885, William L. Austin perfected and patented the first Tosten, Montana Austin process pyritic smelter capable of processing low to medium-grade ores profitably. This state-of-the-art smelter, after modifications and improvements, rapidly became a 25-year game-changer for mining and smelting operations across the Rocky Mountain West and, in particular, Colorado’s Chalk Creek Mining District.

Colonel Morley’s decision to build an advanced pyritic smelter was significant and financially rewarding. The Colonel applied an updated and modernized pyritic smelting technique, beyond Austin’s original patent. He used his own knowledge and skill to more efficiently process lower grades of ore with a reduced requirement for substantial amounts of coal and limestone. Morley’s process oxidized and roasted pyrite ores in a shaft-cold blast furnace, incorporating a mineral flux, specifically copper, to produce a gold or silver metal matte, after the slag was skimmed off. This crude molten mixture of metal sulfides was subsequently transported to, fellow chemistry professor Nathan Hill’s, Denver Argo Smelter for final refining, enabling the full extraction of its precious gold and silver metals. Although a technical and highly profitable success, pyritic smelting resulted in substantial, long-term heavy metals pollution (Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium, etc.). from its slag deposits. Also smokestacks contaminated surface soils in the near vicinity and sometimes at great distances from the smelter site.

Between !887 and 1903, Colonel Morley employed various corporate and financial strategies to facilitate the construction and expansion of the Morley Smelter. Leveraging his background in chemistry, mathematics, and engineering, Colonel Morley engaged in substantial technical discussions with prominent leaders of Colorado’s emerging pyritic smelting scientific community. These discussions included dialogue with Dr. Robert Sticht, Dr. Franklin Carpenter, and other mining and smelting academic and technical experts. Notably, Dr. Carpenter, a former Dean of Faculty and Professor of Geology at the Dakota School of Mines, who also owned the Golden, Colorado pyritic smelter, became one of the Colonel’s most important technical advisors. Furthermore, Carpenter played a significant role as a major investor in Colonel Morley’s pyritic smelter.

It is probable that Colonel Morley transitioned full-time to Buena Vista from Chester during the 1887-1889 construction of his smelter. He arrived in Buena Vista without his family and to a Colorado mountain valley town that had been established in 1879. There is reporting indicating the Colonel returned to Chester from Colorado to teach civil engineering at PMC. When the Colonel decided to return to PMC and for how long he taught engineering is uncertain.

The Colonel’s selection of Buena Vista a small town adjacent to the Arkansas River, as the location for his smelter was likely influenced by the following factors:

The Buena Vista pyritic smelter, designed and constructed by Colonel Morley, was the epitome of technological advancement of its era. Morley integrated his expertise in metallurgy, structural engineering, and the alchemical art of assaying. He also possessed a profound understanding of advanced chemical analysis specifically tailored to pyritic smelters. He quickly achieved remarkable success and profitability, far surpassing the capabilities of other medium-sized pyritic and non-pyritic smelters.

On October 19, 1897, nearly ten years after constructing the smelter, Colonel Morley and his stockholders registered with the Colorado Secretary of State, establishing the Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company. Business operations and Board of Director meetings were conducted in Buena Vista and Chester. Colonel Morley served as general manager, with John Taylor overseeing operations at the Mary Murphy and their other owned Chalk Creek mines. When Colonel Morley assumed full control of the Mary Murphy is uncertain. It is likely that he inherited the Mary Murphy and other mine assets following the 1889 death of J.H. Morley. As mentioned earlier, J.H. believed his nephew to be like his son, and by 1889, Colonel Morley, through his lease arrangement, was well on his way to making the Mary Murphy a financial success. The establishment of this new company was likely to obtain additional stockholders and help fund future smelter expansion to increase daily ore production output.

The Board of Directors of the Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company consisted of the following: Colonel B.F. Morley, Owner, General Manager, and Board of Director, Mary Murphy Gold Mining Company and the Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company; John Taylor, Board of Director of the Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company and General Manager, Golf and Mary Murphy Gold Mining Companies; Henry B. Black, First Vice President and Board Director of Cambridge Bank and Trust, and owner of Chester Edge-Tool Works; J. Frank Black, President and Board Director of Chester National Bank; J.B. Hinkson, Mayor of Chester and Trustee of Pennsylvania Military College, and board director for several banking, finance, and textile factories; George C. Hetzel, Founder of George C. Hetzel Company Woolen Manufacturers; and William Provost Jr., private contractor, builder, and Board Director of Cambridge Bank and Trust.

By 1898, the company’s assessed stock value had reached $250,000. Newspapers from Gunnison to Denver reported that the Chalk Creek and south-central Colorado gold and silver mining industry would have been plunged into collapse without the indispensable contribution of Colonel Morley’s smelter. Within a few years the Morley Smelter had ascended to become one of Colorado’s premier smelting facilities, despite its relatively modest early output capacity of 150 tons per day.

Various collaborating sources, including Colonel Morley, indicate that over $12 million in gold was extracted from the Mary Murphy Mine and refined through his smelter between 1889 and 1900. This figure excludes the additional value gained from other mines partially or wholly controlled by Morley and his associates. Mines from Leadville and South Park also frequently contracted the Morley Smelter due to its superior results and the high-value gold and silver metal mattes produced.

By July 1901, Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company’s stock value had increased from $250,000 to $2,000,000. This growth in stock value is exceptionally high by any standard and would be considered extraordinary for almost any business. It would have reshaped the company’s position in the market and potentially generated substantial fortunes for its early investors and stockholders. Such a stock value would place the Morley Smelter in the medium-cap business category today.

Colonel Morley’s family arrived in Buena Vista in 1893. The Colonel and his family resided in a modest yet comfortable home at the intersection of North Pleasant Avenue and West Main. The house remains extant and is reportedly eligible for state historic designation. According to local accounts, Sarah Elinor participated in the town’s literary society, while the eldest son, Sylvanus, developed a passion for Mayan and Central American archeology as a young Buena Vista student, while exploring the library located at the Colorado State Reformatory, south of town.

From April 1898 to 1900, Colonel Morley served as the elected Mayor of Buena Vista. During his tenure, he enacted several ordinances that significantly contributed to the town’s growth and well-being, including the establishment of telephone service, the provision of electricity, lighting, and heating for residents, the setting of water tap rates, and the enactment of a street and alley ordinance to facilitate town planning and zoning. By this time, Colonel Morley’s smelter had become the town’s largest employer, employing 25% of the available male working population. All electricity generated for the town was sourced from Morley’s hydroelectric dam on the Arkansas River. Additionally, Colonel Morley provided coal for residential and business heating and cooking.

Credible reporting indicates the Morley Smelter was upgraded, probably in 1898, making it capable of processing up to 250 tons of ore per day. This rise in output capacity aligns with a similar increase in gold production at the Mary Murphy Mine. In December 1901, the smelter caught fire, resulting in the destruction of nearly all of the smelter complex. The smelter was insured, and Colonel Morley promptly rebuilt and expanded the smelter’s production capacity. A 180-foot-high brick smokestack was constructed to enhance output capacity and possibly to help reduce the emission of toxic smokestack fumes from reaching Buena Vista. The ore processing capacity, following this upgrade, was enhanced from 250 to 500 tons per day, and the smelter reportedly operated continuously.

In 1900, the American Smelter and Refining Company (ASARCO) implemented an operational strategy to acquire and close all independent Colorado smelters. This hostile takeover business operation was intended to monopolize the market by compelling mine owners to transport gold and silver ores exclusively to ASARCO-owned Pueblo and Denver smelters. According to the June 1902 Engineering and Mining Journal, ASARCO may have attempted a hostile takeover of the Morley Smelter. The Colonel responded promptly by immediately dismissing all 50 employees of the Buena Vista smelter and threatening to close the Mary Murphy Mine as well, potentially idling an additional 100 employees. Morley’s swift response to this potential hostile takeover attempt proved effective, as ASARCO decided not to acquire Colonel Morley’s smelter.

Morley’s Death

On September 22, 1903, while conducting an evening inspection of the lowest, 14th level of the Mary Murphy, Colonel Morley and his mine foreman, Adolph Abrahamson, were overcome by gas and powder smoke left by workers during the day shift. Both men succumbed to asphyxiation before reaching fresh air. Their bodies were discovered by miners upon returning to their shift the following morning. This incident garnered national attention, as it is exceptionally uncommon for wealthy mining executives, such as Colonel Morley, to enter one of their mines, let alone perish within its confines. At the time, Morley had been in the mine acquiring ore samples, utilizing his unique geologic, chemistry, and technical skills to enhance gold and silver output at this new mine adit.

Following the demise of Colonel Morley, an attempt was made to resume operations at the smelter and Mary Murphy under the direction of Colonel Morley’s nephew, R.G. Hinkson. However, without the metallurgical and chemical expertise of Colonel Morley, and a rapid flight of investor capital the financial situation of the smelter and mine began to deteriorate. In 1904, R.G. Hinkson reported to the Chaffee County Commissioners that the company had accumulated a $100,000 debt. Consequently, the corporation promptly closed the smelter and sold the Mary Murphy Mine to a British syndicate for an undisclosed sum. Nevertheless, as late as 1908, John Taylor & Company continued to lease at least portions of the Mary Murphy Mine. This lease may indicate that Chester investors had not fully divested from Chalk Creek gold mining operations. In 1916, the Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company discharged its final mortgage secured on the smelter in 1901, which had been taken out to facilitate reconstruction following the devastating fire.

The smelter’s property, equipment, electric lines, water rights, hydroelectric dam, and electric poles supplying the Town of Buena Vista were subsequently sold to John Eyre, a local former business associate of Colonel Morley. In contrast to many other Colorado mining communities, the Buena Vista Smelting and Refining Company did not simply divest their assets, cease operations, and abandon Chaffee County and Buena Vista with unpaid debts, taxes, and completely hazardous derelict facilities. Presumably, Mrs. Morley, who had spent 10 years befriending members of the community, ensured that all debts were paid, taxes were appropriately allocated, and at least the hazardous brick smokestack was removed. Additionally, electricity continued to be provided to the town until the property was sold to John Eyre.

The Mary Murphy Mine and Morley Smelter provided the Morley family and wealthy investors with substantial profits and rapidly increasing stock values derived from the gold and silver extracted from this region. Upon Colonel Morley’s passing, and within a very short period of time, investors commenced liquidating their company stock, leaving the mine and smelter without the requisite assets to sustain mining and smelting operations. A significant portion of the gold and silver mined, smelted, and refined from the Mary Murphy Mine, between 1880 and 1904, was transferred to various banks and corporations associated with its shareholders. Notably, these companies through mergers, acquisitions, and reorganizations became Wells Fargo and Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna Bank. The Chester Edge-Tool Works underwent several transformations, becoming Ames True Temper, which currently manufactures hand, lawn, garden tools and other non-motorized equipment for consumer use.

Colonel Morley was only 48 years old and did not have a will prepared at his death. Consequently, probate records offer a unique and rare insight as to the wealth of this mining and smelting entrepreneur. It also provides a deeper understanding of his commitment to advancing science and engineering. After settling $10,000 in outstanding debts, Colonel Morley’s 1904 probate decree in Chaffee County included the following assets:

Partial or total mining claim interests in:

Although these amounts may seem insignificant in today’s dollars, they amounted to several million dollars in cash and assets in 1904. This figure does not include the $50,000 personal life insurance policy and millions of dollars acquired by the Colonel and his investors during more than two decades of mining and smelting of precious metals at Chalk Creek and Buena Vista. Estimates suggest the Mary Murphy Mine generated approximately $240,000,000 over its lifetime. Its most productive period spanned from the early-1880s to the mid-1920s, coinciding with the majority of the time James H. and Colonel Morley owned and operated the Mary Murphy Mine and Buena Vista smelter complex. John Taylor’s 1908 lease of the Mary Murphy tunnels may have also increased this figure. The Morley life insurance policy would be equivalent to $1.8 million dollars in 2025. The non-financial item most intriguing in the probate decree reveals Colonel Morley’s enduring interest and passion for science by possessing 74 volumes of scientific books. This action underscores the meticulous care and precision he applied to his academic, scientific, business pursuits, processes, and principles.

Epilogue

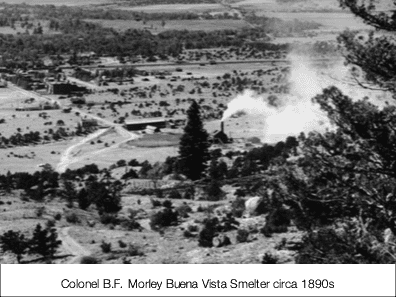

Today, Colonel Morley’s Smelter has been transformed into a Buena Vista Town Park, annually attracting over 100,000 visitors who enjoy the spruce and juniper forests, athletic fields, frisbee golf, a community center, and the opportunity to raft the Arkansas River. The below photo shows the slag foundations of the Morley Smelter at the current Buena Vista River Park.

The Mary Murphy Mine, surrounded by the Pike-San Isabel National Forest, has also become a destination for off-road visitors to the Chalk Creek Creek Mining District. The historic Mary Murphy mining buildings have been removed and the mine remains under private ownership. The Mary Murphy has undergone significant environmental remediation by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to mitigate at least a portion of the toxic heavy metals flowing from its now shuttered mine adits.

The 1881 Morley Railroad Bridge located near St. Elmo is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The bridge has become a site of significant local interest and historic preservation activities. This bridge is Colorado’s oldest dated vehicle truss bridge. It is not inconceivable, that J.H. Morley would have been involved with its design or construction, given his years of experience constructing rail lines across the United States. The mining town of Romley, built by J.H. Morley and expanded upon by the Colonel, to support the Mary Murphy Mine and its employees, no longer exists. In 1868, a small city was named for James H. Morley. At the time, J.H was employed as an engineer to design and construct the southeast Missouri St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad, which included the platted city of Morley, Missouri.

The Town of Buena Vista faces ongoing challenges in assessing the environmental impact of the 20 plus acre Morley smelter complex and associated slag deposits, situated within its town boundary. Buena Vista is currently implementing testing measures to identify potential environmental risks from possible heavy metals.

The smelter complex consisted of several ore loading chutes, a possible stamp mill, used to crush ore into more manageable sizes, an assay building, and the smelter complex itself, located at the end of East Main Street. Slag deposits are found in various locations across the River Park and at the former Morley Arkansas River dam site.

Colonel Benjamin F. Morley’s life in Colorado had a profound and enduring impact on the town of Buena Vista and the Chalk Creek Mining District. The Morley Smelter and Mary Murphy Mine provided a significant source of employment for local residents, lasting for over two decades. This industrial and mining entrepreneur contributed to the development of Buena Vista as both a corporate provider of utility services and as the town’s mayor. Buena Vista acquired a reputation for being a prosperous town at the forefront of modern, scientific-based 1890’s-era industrial processing. The construction of the technologically advanced Buena Vista, Kuenzel process smelter continued this trajectory. Until its design process, which was excessively advanced for its time, ultimately failed, resulting in a 1910 bankruptcy.

James H. and Colonel Morley’s arrival to Colorado in the early 1880’s and the Colonel’s tragic demise in 1903 marked the commencement of a prolonged cycle of economic prosperity and decline for Chaffee County and Buena Vista. The regions population experienced a dramatic decline following the smelter’s closure in 1904 and the closing of many gold and silver mines. For Buena Vista, during the 1920s to 1940s, aside from the long-standing presence of the Colorado State Reformatory, the Town’s primary economic activity consisted of processing and shipping locally-grown irrigated head lettuce. However, the advent of refrigerated railcars led to the collapse of this industry. Of note, much of the electricity used to power the lettuce packing operation came from the Colonel Morley Arkansas River hydro-electric dam. From the 1950s to 1980s, Buena Vista transitioned into a bedroom residential community, primarily dependent on the success of the Climax Molybdenum Mine, located near Leadville. The closure of this mine in the 1980s and again in 1995, further reduced the Town’s population and plunged the local economy into severe financial difficulties. The last railroad ceased operations in 1997 and Buena Vista transitioned into a predominantly summer tourist-based lower-wage service economy. While some new medium-scale industry have arrived in the early 21st century, it is premature to assess the longevity of this trend.

Colonel Morley was a pioneering industrialist, academic, and political visionary who prioritized science, innovation, and education for his family, business, and the local communities where he lived and worked. The impact of his passing had a substantial and enduring effect on the future growth and development of Buena Vista, the Upper Arkansas Valley, and the state of Colorado.

The author, a small business consultant, experienced geomorphologist, retired intelligence officer, and cultural anthropologist resides in Southern Colorado. Sources include a variety of historic newspapers, memorial tributes, biographies, public records, census records, and other similar documents.

Shavano Intelligence Consultant LLC published this historic-cultural article for informational and educational purposes. Use of this article for non-commercial educational and historical use is authorized by the author.

Copyright © 2026 Shavano Intelligence Consulting LLC